It turns out that my friend Marvin takes pills for anxiety. I didn't know this until I found him in the neighborhood bar, which is not his usual place. He was drinking a mug of ginger ale and staring. There was nothing at the other end of his stare: no girl, no TV set, nothing unless you count a patch of the bar's white stucco wall. His eyes looked like they wanted to leave his face, and his mouth had shaped itself into a round hole. He shook his head once, then again, as I said hello to him. On the table in front of him was an old hardcover book bound in green cloth, a book with threads hanging off its spine. It turned out the book was part of the problem, though only part.

Normally Marvin comes across as chipper, not to say buoyant. He's a tall, brown-haired fellow who looks a decade and a half younger than he is, and likes to joke and tease in a light, skipping voice. “Aw jeez,” he says when a male friend shows up. “This one.” Or, to a woman: “Mademoiselle, your presence graces us.” Hey, I didn't say he was funny. He's cheerful and that's plenty. Of course, I don't know why he's cheerful. He has no girlfriend or boyfriend and refers to his apartment as a shoebox. It's around the corner from the cafe, which is where he spends most of his time. He makes his living off his laptop, sitting curled up with it and absorbed in some sort of freelance work he's never managed to explain to me. He told me at some point that he came to Montreal to write a novel, and that the novel, when finished, was rejected by every publisher he could find. Since then no novel, no writing, just the freelance work and the “Hello, mademoiselle.”

I took a seat at his table and asked what he was doing at the bar. “Hi,” he said, which was not quite on point. “Hi there. Hi. I'm all right.” He said this in a way that was light and quick but not at all chipper, and I looked at him more closely. You couldn't tell if he was breathing. His chest didn't move. Just as his eyes seemed to want out of his head, his chest seemed to want to climb up into his throat, and it had got as close as it could and then settled there. He really did not look good.

“Man,” I said, “your hands are shaking.” He took a look at them, as if checking, and that bothered me too. “What's the matter?” I asked.

“Well, you know,” he said. “I take something. My doctor has me on it and we decided to take me off it, and I guess it isn't going so well.” I didn't know he took anything, of course. But he explained. It turns out he's always been highly nervous, so nervous that he feels it has distorted his life. “That's why I thought I was a writer,” he said. “I couldn't do anything else. I couldn't stand in front of a group of people, I couldn't tell anybody what to do, or organize something or... I mean, I get so confused. But I figured I could just hide and write.” A number of years ago, many years ago, his doctor wrote the prescription and Marvin's life became different, or a bit different. “At least I could talk to people. You and I talk. You see me talk to people.” And I have, of course. But, thinking it over, I wonder if I have seen him talk to anybody for long. Or does he say a few chipper things and then dart for cover back in his laptop?

“Look at this,” he said. He pushed the book at me. “Friday,” he said. “Saturday, Sunday. Today. I've been lying on the floorboards in my apartment. I've got the blankets wrapped around me. I lie there. I can't do anything. I think about my life, and nothing has changed. Lying there, I realize I took this drug for 10 years and nothing changed, and now I'm off it and all I can do is go back on it, and when I do I'll still be me.”

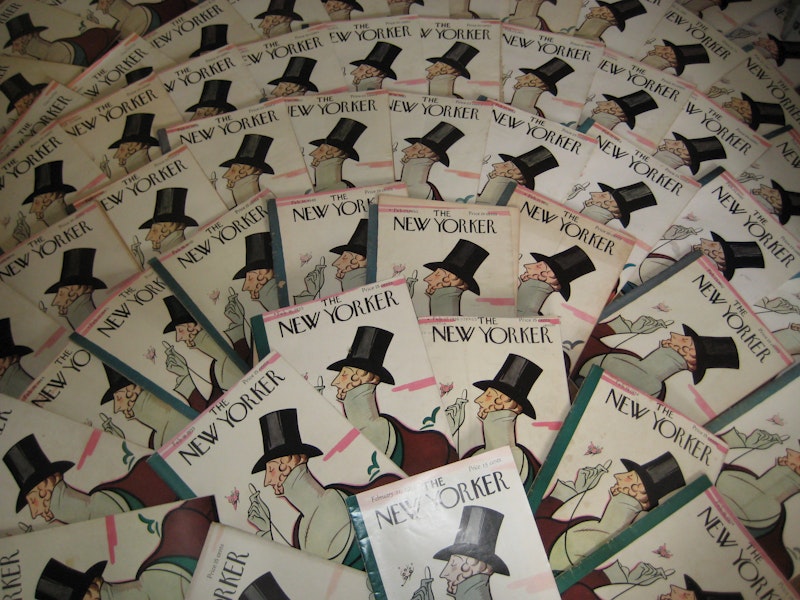

Damn! But I suppose that's why he was in the bar: anything for a change of scene. “What about the book?” I asked. It had an insignia set in the cover, an oval with a profile inside it. “Hey, wait,” I said. “I know that. Eustace Tilley.” You could make out the top hat, the lorgnette, the butterfly. It was the character The New Yorker puts on its cover once a year.

Marvin shook his head again, though not in disagreement. It was more like a minor convulsion had worked its way up through his neck. The skin around his eyes looked like clams. I reflected that I liked him much better when he was chipper.

“I read a few pages of the book, then I lie there,” he said. “I read a few pages, I lie there. All day. The building is quiet, I can't even listen to the radio.”

“At least you have the book,” I said. The paper was rich and had grown brown at the edges. The copyright was 1940 and the title page said Short Stories from The New Yorker. He probably bought it for a dollar or so. There are a lot of used bookstores around.

“There's a story about pelicans,” Marvin said. “This woman just got married and she's starting to realize it was a mistake, and she hates the pelicans on the beach because they remind her of her husband. That's the symbolism.”

“Old-fashioned,” I said, and I leafed through the book—carefully, because of the spine.

“They even have the same smile, the pelicans and the husband. You know, so we don't miss. There's a story about a doorman who goes to see a manta ray at a sideshow, and then he goes home. There's a Dorothy Parker story about a society lady being an ass in front of a black man—you know, all the clichés, like a Norman Lear sitcom.”

“I guess it's dated,” I said.

“I mean, what's the point? English teachers were teaching this stuff, and it's nothing. It's all so simple, except when it's nothing at all. That's what I wanted to do when I was a kid. I thought if The New Yorker published a story, you were somebody. If you wrote something and it was published, you were somebody. And I didn't even know why.”

I thought of saying that at least now it didn't matter about his book not being published. But that would have been mean.

“The pelicans are the husband,” Marvin said. “Wow, subtle.” And his clam-encased eyes stared at the horrible non-subtlety of it all.

“That's why I only read the articles,” I said. It was the only thing I could think of. Still, it's good advice. Then I excused myself. I'll look in on Marvin when he's cheered up again.