We all have our low points; here’s one of mine. At a nerd gathering I heard an adult say the following to a roomful of other adults: “Schama turned that whole idea on its head. He said that it wasn’t the workers, like the Marxists had said. He said the bourgeoisie caused the French Revolution.” No one objected. I didn’t because I’m shy; possibly the others were just ignorant.

Anyway, it was the Marxists who said the bourgeoisie caused the Revolution. Simon Schama, author of Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, didn’t say it. He did have a lot to say about the liberal aristocracy and how they helped get the ball rolling. If I remember correctly, he presents them as hairshirting themselves over their privilege and dramatically casting it aside; as we might say now, it was all very Spirit of 2020. Many of them had families that used to be bourgeois, but that’s not what the Marxists were talking about.

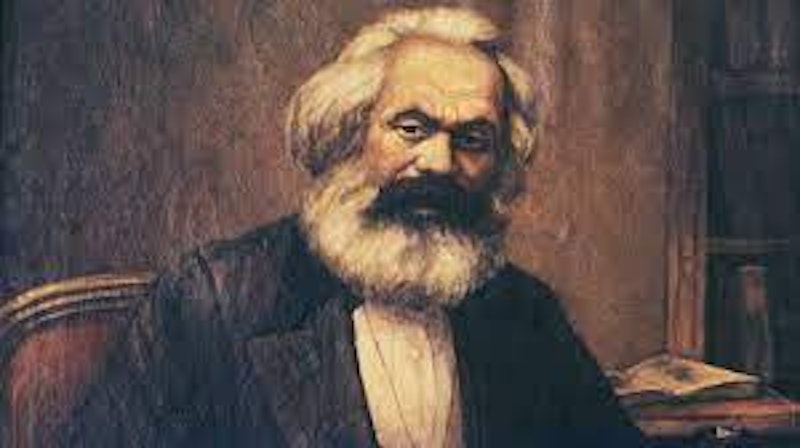

My freshman t.a. told us (“Introduction to European History,” semester one) that the Marxist view of the Revolution came down to a balloon. The bourgeoisie kept growing in wealth and influence until the feudal order ruptured around them. After the rupture, society was remade to fit the middle classes, with a great emphasis on buying and selling and the accumulation of money. To pick up from what I remember of The Communist Manifesto (“Introduction to European History,” semester two), factories will keep multiplying, and the people working there—called the proletariat—will grow numerous enough to remake society once again. It’ll be centered on the needs of labor, with profit eliminated as a factor in life.

Our t.a., and this was long ago, said the Marxist account of the Revolution had flourished for many years before falling prey to further research by academicians. In its day it must’ve looked wonderful. There was the balloon, which is a grabber, and the bourgeoisie had indeed grown in wealth and influence, French society popped, and the new order was clearly more favorable to the middle classes. But certain facts indicated that the bourgeoisie were not the Revolution’s cause. What facts? The t.a. might’ve said, but maybe not. I absorbed a larger lesson, that the fun stuff in academia tends to get its spokes jammed by fragments of truth.

I do know that the guy who talked about Schama’s alleged theory of the bourgeoisie also talks about the Dunning-Kruger effect. I wonder what he thinks it means.

Oh, shut up. I mean, really: “Marx’s discussion of rent is of special importance because it is only a special case of a more general situation which is a great deal more relevant and important today than when Marx originally wrote, namely, the phenomenon of surplus profits generated by monopoly.” I just opened the book and there it was. I open the book again: “The relationship between ‘the changing of circumstances and… self-change’ had been precisely the problem of the traditional materialist view of social change pointed to by Marx in the first part of the third—” I close the book, which is called Marx: An Introduction by W.A. Suchting, University of Sydney. Hands shaking, I think about the lives people lead.