The past dictates the future: on Sunday night, those of us that were born too late to see Twin Peaks end in June 1991 were able to experience the frustration of a finale that not only refused to resolve a dozen loose ends, but went further and annihilated any sense of ease, peace or closure with regard to characters we’ve followed and grown to love. Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) failed in his mission to prevent the murder of Laura Palmer from ever occurring, and in doing so traps himself in an endlessly recursive series of universes, going from timeline to timeline unable to ever completely destroy the enormous forces of evil represented by BOB and Judy. The series finale aired in two parts: Part 17 had something for everyone: opening with Gordon Cole (David Lynch) reading off a list of expository details and tying up a handful of loose threads in the first five minutes. Dale Cooper’s evil doppelgänger “Mr. C” enters the Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department and is promptly shot by Lucy, BOB emerges from his chest and Mr. Green Glove Freddie fights the evil asteroid and seemingly defeats it. Rodney Mitchum (Robert Knepper) breaks the silence: “Well that’s one for the grandkids.” This is all in the first 30 minutes of a two-hour finale.

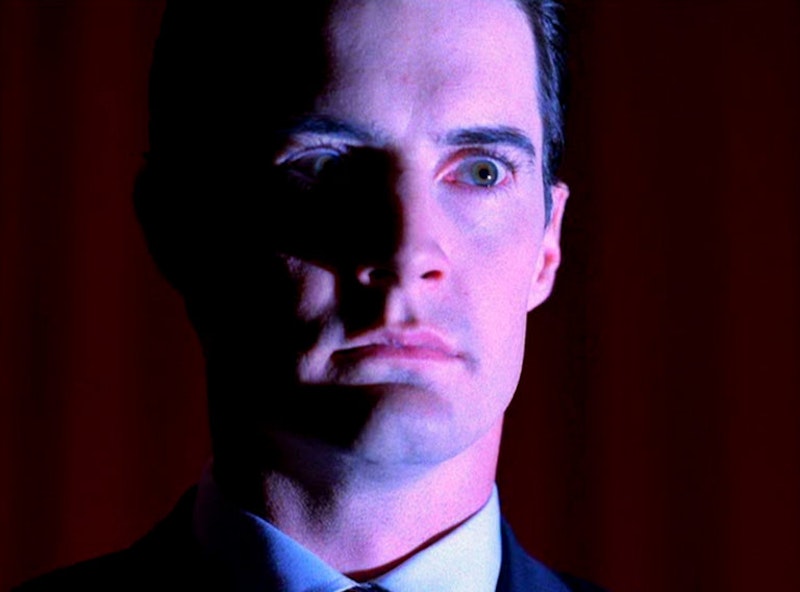

So many things are resolved and coming to a head, but with so much time left, the intensity of those first 30 minutes should’ve been a tip-off that this was going to go off the rails really quickly. Immediately after that battle, there’s a sequence that was so intoxicating and breathtaking, I’d tentatively rank it among the greatest work Lynch has ever done: after evil has seemingly been defeated, the camera goes in for a close-up on Cooper’s face, the frame freezes, and the rest of the scene plays out with a loop of Cooper’s alarmed and confused face in close-up, subtly super-imposed over the room. This is when things start to sink, and even as I was caught up in the ecstasy of this movement, I should’ve known. But the fan in me thought, “Oh, this is great. We’ll get to see where Audrey is. There’s no way they won’t revisit her after that cliffhanger last week showing her in a white place, either limbo or an institution or one of the Lodges.” Nope.

That’s the last we see of Audrey Horne: one last reprisal of her dance in the Bang Bang Bar, a way-station for lost souls, and then a jolting back to consciousness in that white place. Leaving the audience hanging with that—I mean, it would’ve been brutal enough to leave Audrey stuck in that room with her prick husband Charlie, unable to leave—it’s something that no other show would do. Ever. Because that is the most “Fuck You” option—tease you to the point of epiphany only to be cut off and denied release. Only David Lynch could’ve gotten away with this kind of ending in a post-Sopranos landscape of prestige TV.

Ever since David Chase bravely decided to end his show ambiguously with an abrupt cut to black, people have played it safe to a fault: the creators of Breaking Bad and Mad Men were acutely aware of fan expectations and managed to end those shows in ways where no one could really get mad. Which is fine, but after getting what you want, you don’t think about it very much after the fact. It’s been consumed and understood, there’s nothing left to dwell on. Twin Peaks: The Return was a rebuke to that mindset, of kowtowing to the audience and indulging in nauseating fan-service that just ends up feeling like eating a garbage bag full of candy.

Lynch and his collaborator Mark Frost were warning us the whole time: “the past dictates the future.” Events in Twin Peaks: The Return are presented out of order and without context, and it’s obvious to me that the final scene of the show is not the chronological ending. People will be writing insane mad-scientist theories on the Internet for years to come, but for now, fans are still processing their visceral reactions to a show that teased an “ending for everybody” and concluded with the seemingly all-knowing, always competent, noble, and indefatigable FBI Special Agent just as flummoxed and lost as the audience, sunk even lower in warped space time, trying to save Laura Palmer forever and just getting more and more metaphysically fucked up as he continues to try.

Ending the series with the most clichéd cliffhanger line imaginable—“What year is it???”—was bold, and as the electricity blew out in the Palmer house and the show cut to black and the credits rolled over that close-up of Laura whispering into Cooper’s ear, I let out a long sigh, feeling an intense vicarious anxiety, knowing how pissed off thousands of people would be. Some friends of mine that went to watch the finale at The Parkway confirmed my worst fears: a packed house full of emotionally charged fans who were ecstatic through Part 17, and went silent as Part 18 unfolded.

The frustration and lack of completion I felt as Part 18 ended is beginning to make more sense, even if the conclusion remains unbelievably bleak: Dale Cooper failed. In his own hubris and ignorance, he thought he could erase the trauma of Laura Palmer’s life in addition to her murder. But you cannot erase suffering. Laura—in the form of Carrie Page—carried the trauma inflicted upon her by her father Leland through an infinity of timelines, and if Cooper continues on this path, he’s doomed to repeat his own mistakes and just continue to make things worse.

Twin Peaks: The Return cannot be compared to other prestige TV shows because there was never another season in the works. This was it. There was never any pressure from the network or from fans to wrap it up a certain way, as if Lynch would’ve listened to anyone but himself. The nihilistic ending shook us out of the warm, comforting, and entertaining aspects of The Return: seeing Ed and Norma kiss over Otis Redding; Bobby Briggs as a cop, grown up and responsible and atoned; Lucy and Andy happily married with a grown child they’re very, very proud of. I take solace in the beginning of Part 18, where we see Dougie return to his family: Cooper’s sacrifice in improving Dougie’s life and the lives of his family mitigates the existential hell of his own ending—and I was relieved when Mr. C killed no one in the Sheriff’s Department, especially Andy. Oh my god, Andy and Lucy made it out unscathed. If they didn’t… well… I would be writing Mr. Lynch a very stern letter! Express mail!

Twin Peaks: The Return has no precedent and nothing is likely to follow in its footsteps: it’s a sickening and challenging meditation on evil, and in the end, evil won. But we can debate this for hours, for years to come. As I sat down to write this last night, I got a call from my friend John, and we ended up talking for nearly two hours about the finale and its implications. Film programmer Eric Hatch noted that, like Mulholland Drive, which came out nearly 16 years ago and still invites frequent analysis and new interpretations, the 18-hour serialized film that is Twin Peaks: The Return will be debated and discussed long after the 71-year-old Lynch has passed away, and if this country ever gets another artist as interested in facing evil and frustration and dissatisfaction and disappointment as pointedly as Lynch did in The Return—well, let’s treat them with some respect and give them some space, and not repeat what ABC did to the original run of Twin Peaks.

I’m not eager to re-watch The Return any time soon—it’s too disturbing, too sickening to continually revisit—but I do want to watch Part 8 again before my Showtime subscription expires at the end of the month. Knowing how it all plays out, a dive into the heart of a nuclear explosion might be the most cathartic thing to experience, and another look at the “Drink full” speech that the charred Woodsman intones over the radio in black and white New Mexico. The Return is Lynch’s masterpiece, and while it’s not fair to compare an 18-hour movie to one of his feature films—the best is Mulholland Drive if you ask me—few artists have reemerged with such a massive career-spanning work in the twilight of their years. Forget Blackstar—this is the way you go out.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992