The Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski is more than a movie: it’s a sort of spring tonic to cure what ails me. In a wonderfully absurd touch, Sam Elliott, iconic in dragoon moustache, chaps, and cowboy hat, asks a bowling alley bartender for a sarsaparilla, a request no 19th-century bartender would’ve considered odd. Sarsaparilla, though medicinal, contained sufficient alcohol to appear on a saloon’s back shelf.

Victorian America believed in spring tonics: medicines to eliminate poison from the blood and tissues, purifying the system of all leftover infelicities of winter, and rehabilitating the body for the rest of the year. The practice endured into the mid-20th century: my father’s parents forcibly dosed him with a mixture of sulphur and molasses to cleanse the blood. Sarsaparilla was an attractive alternative to such revolting home remedies.

The beverage was distilled from its eponymous plant’s root. Known to botanists as Smilax medica, the sarsaparilla is a thorny vine that flourishes in Central and South America, Mexico, and the Old Southwest. Its name is a Spanish compound: sarza (bramble) and parilla (little vine). The 19th century American Puritans who guzzled it for aches and pains were probably unaware that sarsaparilla had first been introduced into European pharmacology in 1536 as an absolute specific—a complete cure—for syphilis. It wasn’t. Two centuries later, sarsaparilla was revived as what physicians then called an alterative, something tending to change a “morbid state into one of health.” It became known as a blood purifier and medicine for spring. Evidence of early American medicine’s informality is that an entirely different plant, wild sarsaparilla, Aralica nudicalis (also called American/Virginian/false sarsaparilla, rabbit root, or wild licorice) was used in compounding spring tonics because its roots resembled those of Smilax medica.

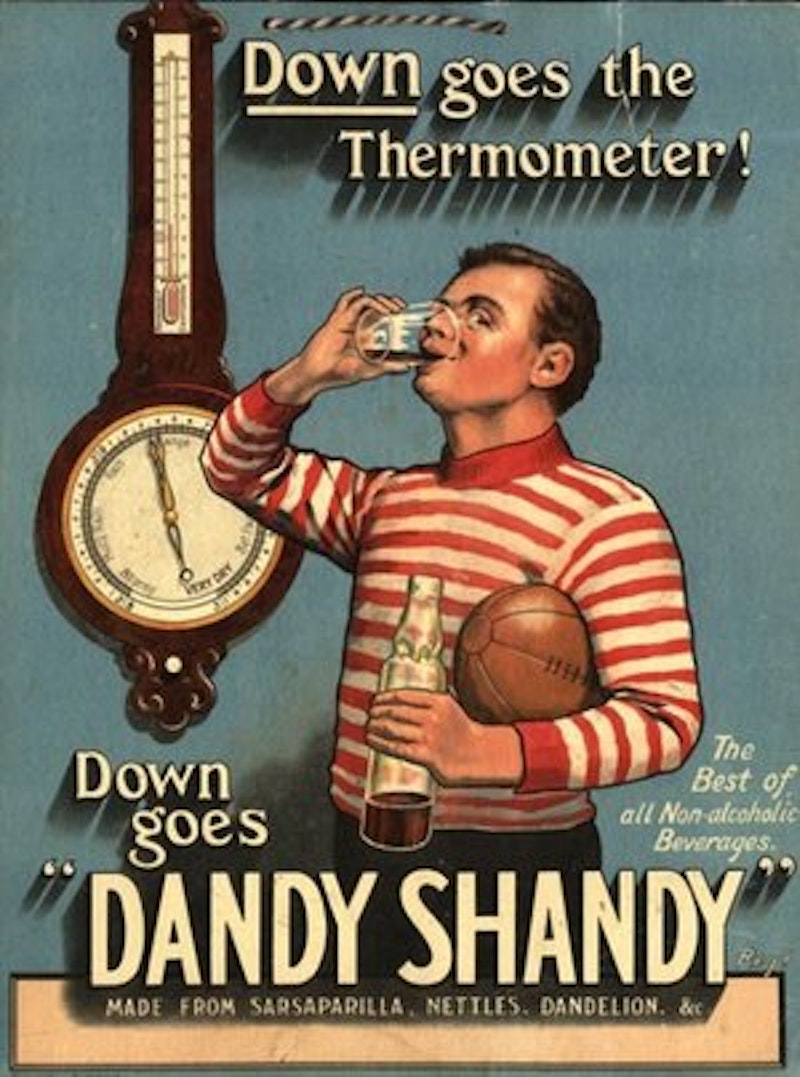

By the 1850s, the dark, fragrant, naturally foamy beverage distilled from sarsaparilla root was probably the most popular patent medicine in North America (“patent,” when applied to medicine, stemmed from royal patents issued during the colonial era that granted the holder an exclusive right to market a particular medicine; most post-Revolutionary patent medicines were trademarked rather than patented because exclusive rights to a patented formula then expired after 17 years). By then, sarsaparilla’s advertisers claimed it also cured upset stomachs and the common cold and eased aching joints. Some said it would cure anything short of a gunshot wound (and, even those claimed that applying powdered sarsaparilla root directly to the bullet hole could only help). By the 1880s, numerous brands competed for business across the country. Their advertisements presented them as vegetable tonics, making them seem more natural and health-giving, and suggested that any infraction of the Laws of Nature (tactfully left undefined) might be mended by immediately and consistently consuming the right brand of sarsaparilla.

This shameless advertising reflected ruthless competition. Bristol’s Sarsaparilla, produced by C.C. Bristol of Buffalo, NY, was described as being of “celebrity almost without precedent” and had triumphed over illness in the worst cases, “bringing approval of the medical faculty.” Dr. Easterly’s Sarsaparilla was “Six Times Stronger” than any other brand and had cured more than 25,000 cases of disease within three years, including “3,000 of scrofula, 2,000 of dyspepsia, 1,000 gout and rheumatism, 2,000 general debility, 2,500 liver complaint, dropsy, and gravel; 1,500 female complaints; and 6,000 syphilitic or venereal coughs.” And why should one dodder along with a mere sarsaparilla when one might use Dr. Radway’s Sarsaparillian Renovating Resolvent?

People used these nostrums because then, as now, a physician’s prescription was more expensive than an over-the-counter remedy. Moreover, in the absence of nearby physicians, frontier settlers often had to doctor themselves. Finally, even legitimate M.D.s seemed little removed from quacks. As late as 1870, Dr. Calvin Ellis, dean of the Harvard Medical School claimed, “written examinations could not be given because most of the students could not write well enough.” Shortly afterwards, he received a letter from Charles Warren Eliot, the University’s President, requiring that Dr. Ellis implement written examinations, which he did.

Perhaps the best selling sarsaparilla was Ayer’s, which became famous through massive advertising. James Cook Ayer, M.D. (University of Pennsylvania, 1841), began compounding remedies in the back room of his drugstore in Lowell, Massachusetts. By 1870, he was advertising his products in 1900 newspapers and magazines. He filled hundreds of thousands of bottles daily, labeled them with paper from his own mills, and shipped them to the entire world on his own railroad. He billed Ayer’s Sarsaparilla as "a medicine of such concentrated curative power that it is by far the most economical and reliable medicine that can be used..." He claimed it could help with "tired feelings... which are the result of an impure, impoverished, or scrofulous condition of the blood," and was the best remedy for dyspepsia, liver and kidney diseases, jaundice, and dropsy.

Still, J. C. Ayer was only one of hundreds of patent medicine manufacturers. In New York City, Dr. Brandreth’s Vegetable Universal Pills employed dozens of workers in its Broadway factory covering a square block.

Patent medicine advertisements filled the leading newspapers and magazines and covered the sides of barns and cliffs. For example, the March 5, 1914 issue of the Antrim Reporter, a New Hampshire rural weekly with a circulation of a few hundred, had 18 advertisements for patent medicines, six of which were set in ordinary type as if they were news stories with the abbreviation “Adv.” at their ends. Examining period newspapers with an eye toward the advertising might lead one to believe everyone suffered from Female or Male Weakness, Worn-Out Kidneys, or Consumption. These were, if one credited the ads, best treated through self-medication with over-the-counter nostrums such as Texas Charlie Bigelow’s Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, Doc Hamlin’s Wizard Oil, or Cram’s Fluid Lightning.

There was a reason why sarsaparilla was said to cheer as it cured. Like most patent medicines before the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, sarsaparillas contained amazing amounts of alcohol. This may explain one quality attributed to good sarsaparilla: it never froze, regardless of the temperature. Such nostrums as Dr. Hostetter’s Celebrated Stomach Bitters were 94 proof. Others, such as Dr. King’s New Discovery for Consumption, “the Only Sure Cure for Consumption in the World,” mixed morphine (to suppress coughing) and chloroform (a euphoriant) so as to control the symptoms of tuberculosis without treating the illness.

By then, Establishment opinion dismissed sarsaparilla as a medicine. The 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica described it as “pharmacologically inert and therapeutically useless.” In the same year, the Connecticut State Agricultural Station, after analyzing Ayer’s and eight other medicinal sarsaparillas, found they were “of a most complex composition, containing not only sarsaparilla, but yellow dock, stillingia (another “blood-cleansing root”), burdock, licorice, sassafras, mandrake, buckthorn, senna, black cohosh, pokeroot, wintergreen, cascara sagrada, cinchona bark, prickly ash, glycerin, iodids of potassium and iron, and alcohol.” Although some of these ingredients had medicinal effects (quinine comes from cinchona bark; senna and cascara sagrada are gentle cathartics), the Journal of the American Medical Association consequently argued sarsaparilla was so compounded as to be useless, though generally harmless.

The Pure Food and Drug Act devastated the patent medicine industry by reducing the legally permissible alcohol content of patent medicines to 25 percent. Nonetheless, medicinal sarsaparilla enjoyed a brief revival during Prohibition. After all, a beverage that’s 25 percent alcohol by volume is still 50 proof. But after Repeal in 1933, sarsaparillas fell into desuetude. Many argue that today’s root beers, flavored with sassafras, are indistinguishable from sarsaparillas. However, the handful of manufacturers who still brew sarsaparillas, most with self-consciously cute names such as Ol’ Bob Miller’s Sass’parilla, argue that their products are true sarsaparillas, made only from the root of Smilax medica, with a gentler, less overpowering taste than root beer, which can be compounded from mixing nearly any imaginable roots, herbs, or barks. Somehow, it all seems immaterial: Ol’ Bob Miller’s, like A. J. Stephen’s Olde Style Sarsaparilla, Crazy Ed’s Original, Baron’s Boothill, Old Mill, SodaWerks by Dirty Dawg Sass’parilla, or Hansen’s Sarsaparilla (sold in a 14-oz. bottle that, according to one on-line critic, resembles “an uncircumcised penis”), consists largely of distilled water, vanilla extracts, a natural sweetener such as honey or cane sugar, and artificial flavors, with sarsaparilla added only as a natural flavoring. Even the water is carbonated: apparently, the manufacturers don’t use enough sarsaparilla root to make the beverage naturally foamy. And none contain alcohol.

But whether used as a powder or a tea, externally or internally, sarsaparilla root enjoys revived interest among New Agers as a treatment for a bewildering variety of ailments. One website dedicated to natural medicines claims sarsaparilla is “good for gout, rheumatism, colds, fevers, and catarrhal problems, as well as for relieving flatulence… skin problems, scrofula, ringworm, and tetters… purifies the urino-genital tract… has tonic action on the sexual organs... is said to excite the passions, making men more virile and women more sensuous… it can be used as a wash for genital sores or herpes, or as a hot fomentation for painful, arthritic joints.”

Sounds just like an advertisement from the good old days.